Eric Bruneau

Eric Bruneau

“This year a joint delegation of the Syrian government and the Baath party came to the Newroz celebration”, says Mr Abdulbaqi, a member of the Kurd opposition party PYKS. “The Kurdish flag was up in their presence.” It is an event in Syria, where Kurds are victims of state discrimination. An important number of them are denied citizenship, and carrying a bracelet with the Kurdish colours can earn the “offender” 6 months to one year in jail. Newroz, the Kurdish New Year held the 21 of March, regularly sees the police brutally dispersing the celebrations, often using live ammunitions. “And it was at Qamishli”, adds Mr Abdulbaqi.

The fact that this delegation came to Qamishli is even more startling. In this town on the Turkish border, the 12/03/2004, clashes opposing Kurds and Arabs provoked the intervention of the army. 35 Kurds were killed, some being allegedly tortured to death. Since, yearly commemorations see clashes between security forces and Kurd militants.

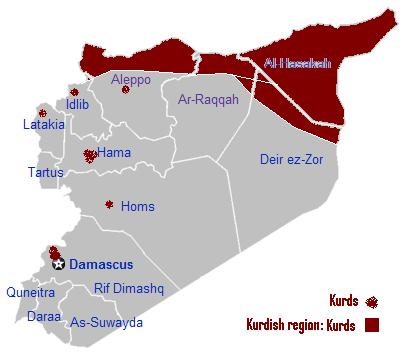

This year, there was an ominous sign indicating the government was bracing itself for a new confrontation. The 47th regiment moved from Homs to the Kurdish province of al-Hassaka the 02/03/2011, and since January, military posts were built beside each of the Afrin province Kurdish villages which rose up in support of the Qamishli people in 2004.

But nothing happened. A demonstration in Qamishli gathering around 10000 people went peacefully, without any provocation from the security forces. The following day, the 13/03/2011, the streets were notably empty of any military presence. “It is because the Baas regime is afraid”, said then Mr Hesso. “It fears to be the next one to be swept by the wave of Arab revolutions.” Mr Hesso is a member of the PYD, a party attracting the most radical amongst Kurdish militants, with close links with the Turkish-based PKK. Still recently, he was a political detainee, and he says he was released in a governmental effort to keep the Kurds quiet. “The government fears that an incident in the Syrian Kurdistan would spread unrest in the whole of Syria. So it releases political prisoners, opens negotiations, this kind of things.” This same 13/03/2011, talks were held in al-Hassaka between the government and the PYD. And Mr Hesso, who even if he was out of jail was meant to stay inside Qamishli, was invited to Damascus by the Syrian Communist Party, acting on behalf of the Baath ruling party. But, he was explaining, it was delaying tactics. Once the crisis will be over, things will go back to normal: repression will resume. The regime just wants to buy time.”

For signs of agitation amongst Kurds have caused concerns in president Bashar al-Assad’s government. In January, the death of two PYD militants in an army ambush provoked riots in Aleppo and Damascus, were several police vehicles were burnt. Some political detainees from the PYKS, PYD and Azadi party started a common hunger strike with some Arab political prisoners. And recently, the 29/03/2011, the Kurdish Council in Syria, a coalition of 9 Kurdish opposition parties, gave a statement demanding equality of citizenship, a democratic regime, and the right for self-administration.

However it is in the Arab south that riots erupted. And now that they are spreading to the rest of the country, the Kurdish north remains strangely quiet. Mr Abdulbaqi explains this silence by the fear to see the Baath regime turning a Kurdish uprising to its advantage. “For decades Damascus imposed Arab colonists in Kurdish territory. These colonists have weapons, and if Kurds are taking to the streets, it is to those militiamen that we will be opposed rather than to the army. It would be for president Bashar al-Assad and his generals the opportunity to turn the riots in a racial war. We will not give them this chance.” The Kurds would join in the riots, he added, when they will reach the big towns, like Aleppo, Damascus or Hama. Until then, the Kurds will not give the government the opportunity to turn the Arabs against them.

This caution of the Kurdish opposition illustrates the distrust between them and the Arab opposition. Saleh Muslem, the PYD general secretary, went to talk in 2004 to Heytham Malih, a prominent Arab dissident, to propose an alliance. Heytham Malih refused, telling him he was “an agent of the Zionists and of the Americans.”The Arab opposition”, was saying Mr Saleh, interviewed the 18/03/2011, and has the same nationalist mentality than the Baas. They see the Kurds as separatists who have to be assimilated in an Arab nation.” So if ever the Baas regime loses the power, what will come after? There will be a change for the minorities in Syria or there will be another Arab – centred state? “There is nothing certain”, says Mr Abdulbaqi. “But if President al-Assad’s Allawi minority loses the power, they will do anything to have a confederalist system, and so secure an Allawi state: they are very afraid of a Sunni government. The Druzes are favouring this solution too. Of course, we Kurds want it too, for we want to administrate our own territory: we do not want to be submitted to a central government any more. A decisive step has been made, we will not back down.”

The desire of the Syrian state to keep the Kurds quiet can also been explained by its fear to see coming back, at the worst moment ever, some of the 1500 Syrian Kurds present nowadays in the PKK guerrilla army. “During ages, relations between Turkey and Syria were very bad, to the point that president Hafez al-Assad (father of the present president), allowed the PKK rebels to build training camps in Syria.” are explaining the Kurds. “It was for the Syrians to wage war to Turkey without committing themselves, and to send the most combative Kurds to get themselves killed. And while they were busy battling in Turkey, those Kurds were not demanding for rights in Syria.” “It explains the emergence of the PYD. Until Hafez al-Assad expelled the PKK in 1998, it was a normal thing for a young Syrian Kurd to join the PKK. Our base, it is the families of PKK Syrian members.” added Mr Hesso. He knows it very well himself: one of his sons died in action, another one went to the guerrillas past year, with a group of 60 volunteers.

The power of the organisation (during the last Qamishli commemoration, are saying its spokespersons, 5 to 6000 of the demonstrators were PYD supporters), its ability to mobilise crowds and its links with the revolutionary PKK clearly scares the Syrian government. In 2007, a project to impose 250 Arab families in Kurdish populated Deyrick had to be suspended, by fear of an open conflict with the PYD. But, insists Mr Saleh, the organisation doesn’t have any armed wing, and its members are under strict instructions not to go into a fight with security forces. “But it depends as well from the government’s attitude. If it attacks our population, a deterioration of the situation will occur.”

The Baath regime could take pretext of any incident with the PYD to claim being attacked by the PKK, and so provoke a Turkish intervention. For Damas has now very good relationship with Ankara and they have together numerous cooperation agreements, notably in the domain of security. “The Turks will not accept in Syria a federal solution giving self-administration to the Kurds, judges Mr Abdulbaqi. They will do anything to control the change which is happening. They will use their influence on the Syrian government and on some communities to implement their own agenda in the country.” As to back his claims, the director of the MIT, the Turkish secret services, recently went to Damascus to advise the Syrian government about how to manage the crisis.

Countless scenarios are so possible, depending not only from the outcome of the present riots, but as well from external forces. The Kurds, anyway, are expecting radical changes, and are keeping their attention focused on the great cities.