REPORT, — Approximately 1.7 million Kurds live in Syria, a much smaller number than in Turkey, Iran, or Iraq. Furthermore, the Kurds in Syria live in three non-contiguous areas and, therefore, historically have been much less successfully organized and developed than in the other three states. Nevertheless, the Kurds in Syria constitute the largest minority in Syria. For many years the repressive Syrian governments of the Assads have sought to control their Kurdish minority by various oppressive means including an Arab belt between its Kurds and those living in neighboring Turkey and Iraq. Some Kurds have also been denied Syrian citizenship (the so-called ajanib), while others have been stripped of their basic civil liberties (the so-called maktoumeen).

REPORT, — Approximately 1.7 million Kurds live in Syria, a much smaller number than in Turkey, Iran, or Iraq. Furthermore, the Kurds in Syria live in three non-contiguous areas and, therefore, historically have been much less successfully organized and developed than in the other three states. Nevertheless, the Kurds in Syria constitute the largest minority in Syria. For many years the repressive Syrian governments of the Assads have sought to control their Kurdish minority by various oppressive means including an Arab belt between its Kurds and those living in neighboring Turkey and Iraq. Some Kurds have also been denied Syrian citizenship (the so-called ajanib), while others have been stripped of their basic civil liberties (the so-called maktoumeen).

However, the emergence of the KRG has helped begin to change this situation. For example, within days of becoming the president of the KRG in June 2005, Massoud Barzani demanded that the Syrian Kurds be granted their rights peacefully. This call has perhaps helped galvanize the Kurds in Syria into creating new pro-Kurdish organizations and taking a more active role in demanding changes to their previous situation. The purpose of this paper is to analyze the current situation of the Kurds in Syria. It also examines the Decree 49 and the development after the Qamishli-uprising in 2004. Finally, the authors call for action to be undertaken by on the Syrian Government in order to change for the better the situation for all peoples of Syria – the Kurds included.

Kurdish history shows that at the end of World War One, consideration was given to formally declaring that Kurds would be given control of their historic homeland, however this was never endorsed and subsequent treaties led to the division of Kurdistan and its people among the four countries of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. In this paper we focus on the latter.

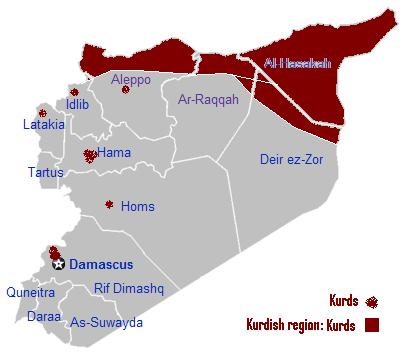

Approximately 1.7 million Kurds live in Syria, a much smaller number than in Turkey, Iraq, and Iran. In Syria, the Kurds live in the northern area on the border with Turkey in the area we call Western Kurdistan which includes the areas of Kobani and Afrin in the north of Aleppo, and Hassaka province, and large numbers of Kurds are also living in other parts of Syria including Damascus. Although the largest minority in Syria, the Kurds live in three non-contiguous areas and seems to have been much less successfully organized and developed than in the other three states. For many years the repressive Syrian government of Hafez Assad sought to maintain an Arab belt between its Kurds and those in Turkey and Iraq. This Arab belt uprooted many Syrian Kurds and deprived them of their livelihoods. There are no accurate official statistics on the number of Kurds in Syria because the Syrian government considers everyone to be Syrian-Arabic. Latest estimates indicate that Kurdish people constitute about 15% of Syria’s population, amounting to nearly three million people. Many Kurds in Syria have even been denied Syrian citizenship.

In August 1962, Decree 93 was brought into force as a result of which a census was taken on 5 October 1962. At that time, however, the authorities arbitrarily refused to register 120-150,000 Kurds in the Hassaka region. These people and their descendents remain stateless within Syria and their number has grown to more than 300,000. The situation for stateless Kurds is of considerable concern as they are deprived of basic human rights. Some are called ajanib or foreigners who could not vote, own property or work in government jobs. This group is given a red identity card, others – some 80,000 Kurds are known as maktoumeen or concealed and they have nothing. As such, they have virtually no civil rights.

A secret resolution from 1981 prevents stateless Kurds being employed in the civil service. In 1991 Minister of Higher Education issued circular 678, which prevents the admission of stateless students to all schools and institutes. Further decrees followed to prevent stateless Kurds owning property. The daily lives of the 80,000 maktumeen, and are extremely difficult due to the numerous ways in which they are denied basic necessities of life. Food aid delivered to Syria by the international community to assist during the drought has not been available to stateless Kurds because they do not have citizenship, and the Kurdish areas do not appear to have benefitted anyway.

In this way the Syrian Government has deprived Kurds of their historic homelands. In 1963, Lt. Muhammed Talab Hilal, the chief of the security police in Hasaka, printed a book in Arabic entitled National, Political, and Social Study of the Province of Jazira, in which he outlined how to disperse and marginalize the Kurdish population in Syria. This book changed the demography in the Kurdish area by the idea of displacing Kurds and crating Arab villages. The idea was later adopted by the Ba’ath Party resolution no. 521 of 24 June 1974. Arab families were brought from Aleppo and al-Raqqa to displace tens of thousands of Kurdish peasants by force.

The book was kept secret but Professor Ismet Cheriff Vanly obtained a copy and revealed its anti-Kurdish contents. For example, Hilal argued that people such as the Kurds have no history, civilization, language, or ethnic origin and are prone to committing violence like all mountain people. This is similar to the way Turkey has abjured its Kurdish citizens. Thus, the Kurdish question has become a malignant tumor on the Arab body politic and needed to be excised. Further, the Kurdish question was the most dangerous threat to the Arab nation, especially the Jazira region and northern Iraq. Hilal compared the Kurdish question to the Zionist movement before the establishment of the state of Israel.

Kurds in Syria are forced to learn and speak Arabic and the use of Kurdish is forbidden, but Kurdish dialect called Kurmanji has survived within families and communities where children are taught in secret. A government decree in September 1992 prohibited the registration of children with Kurdish first names. Kurdish cultural centers, bookshops, and similar activities have also been banned. For all these reasons, therefore, little was heard about the Kurds in Syria.

Events in Kurdistan of Iraq, however, have had some positive influence on the situation. In March 2004, Kurdish rioting broke out at a football match in Qamishli (see also p. 5). Since then, the atmosphere has remained tense. Renewed rioting occurred one year later in Aleppo following the killing of Maashouq al-Haznawi, an outspoken Kurdish cleric critical of the regime. Within days of becoming the president of Kurdistan in Iraq in June 2005, Massoud Barzani demanded that the Syrian Kurds be granted their rights peacefully. The forced Syrian troop withdrawal from Lebanon following the assassination of the former Lebanese prime minister, Rafiq Hariri, in February 2005, a strong UN Security Council response to apparent Syrian involvement in the affair, and the U.S. occupation of neighboring Iraq have also presented grave international challenges to the Syrian regime. Bashar Assad – who had succeeded his father when he died in 2000 – indicated that he was willing to entertain reforms, but has not offered any specific timetable. Thus, as of the end of 2010, the Syrian Kurds are showing increased signs of national awareness partly due to the developments in the KRG, but remain much less successful implementing them than do their brothers in Iraq and Turkey.

CURRENT SITUATION

As also mentioned above Syria’s Kurds held large-scale demonstrations in March 2004, in a number of towns and villages throughout northern Syria, to protest their treatment by the Syrian authorities—the first time they had held such massive demonstrations in the country.5 While the protests occurred as an immediate response to the shooting by security forces of Kurdish soccer fans engaged in a fight with Arab supporters of a rival team, they were driven by long-simmering Kurdish grievances about discrimination against their community and repression of their political and cultural rights. The scale of the mobilization alarmed the Syrian authorities, who reacted with lethal force to quell the protests. In the final tally, at least 36 people were killed; most of them Kurds, and over 160 people were injured. The security services detained more than 2,000 Kurds (many were later amnestied), with widespread reports of torture and ill-treatment of the detainees.

The March 2004 events constituted a major turning point in relations between Syria’s Kurds and the authorities. Long marginalized and discriminated against by successive Syrian governments that promoted Arab nationalism, Syria’s Kurds have traditionally been a relatively quiet group (especially compared to Kurds in Iraq and Turkey). The protests in 2004, which many Syrian Kurds refer to as their intifada (uprising), as well as developments in Iraqi Kurdistan, gave them increased confidence to push for greater enjoyment of rights and greater autonomy in Syria. This newfound assertiveness worried Syria’s leadership, already nervous about Kurdish autonomy in Iraq and increasingly isolated internationally. The authorities responded by announcing that they would no longer tolerate any Kurdish gathering or political activity. Kurds nevertheless continued to assert themselves by organizing events celebrating their Kurdish identity and protesting anti-Kurdish policies of the government.

In the more than six years since March 2004, Syria has maintained a harsh policy of increased repression against its Kurdish minority. This repression is part of the Syrian government’s broader suppression of any form of political dissent by any of the country’s citizens, but it also presents certain distinguishing features such as the repression of cultural gatherings because the government perceives Kurdish identity as a threat, as well as the sheer number of Kurdish arrests. Decree 49 signed by the President was brought in on 10 September 2008 and places stricter state regulation on selling and buying property in certain border areas. It mostly impacts Kurds and is perceived as directed against them. Decree 49 further limits the use of the land in the Kurdish area on the pretext of controlling terrorism, such that a license had to be obtained for use of the land for building etc however since the law came into force, Kurds have not been granted licenses whereas others have. This is a deliberate policy to drive Kurds out of their homelands by destroying their construction industry, forcing people to move to the cities to find work to survive. In addition, agricultural industry which is the other main source of sustainable life for Kurdish families is under significant threat as a result of drought, and the retention of water by Turkey. State aid is not coming for these families, and thousands of families have left the area.

The Syrian government has sought to ban demonstrations for Kurdish minority rights, cultural celebrations, and commemorative events, as well as stepping up the mistreatment of detainees and continuing the lack of due process protections in their prosecutions. Since 2005 up to the present, Syrian security forces have repressed at least 14 political and cultural public gatherings, overwhelmingly peaceful, organized by Kurdish groups, and often have resorted to violence to disperse the crowds. In at least two instances the security services fired on the crowds and caused deaths, but did not order any investigation into the shooting incidents. The security services even investigated a group of Kurdish secondary school students because they held a five-minute vigil on March 12, 2008, to commemorate the March 12, 2004 events at the soccer stadium in Qamishli, which ignited the 2004 protests.

The security forces have not only prevented political meetings but also cultural and social gatherings. Kurds celebrating the traditional Newroz (the Kurdish New Year), were shot in the street by the authorities in March 2008 and 2010. But it could as well have been celebrations to mark human rights day, or demonstrations to protest the treatment of Kurds in neighboring countries. Kurdish conscripts are dying in mysterious circumstances, eleven died in 2010.

Syria’s security services have detained a number of leading Kurdish political activists. While they detained some for only a few hours, they referred others to prosecution, often before military courts, which have sentenced them to prison terms. A Kurdish activist told Human Rights Watch, “There used to be a red line on detaining known Kurdish political leaders. But since 2004 this line is no longer there.” Human Rights Watch has documented the arrest and trial of at least 15 prominent Syrian Kurdish political leaders since 2005 to the present, including those involved in Kurdish political parties, including dozens of members of the Democratic Union Party – PYD (Hezb al-Ittihad al-Dimocrati), a party closely affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey.

Syrian security forces have detained activists without arrest warrants by relying on the country’s Emergency Law, in place since 1963. All 30 former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that security forces initially held them in incommunicado detention while interrogating them. It was only after their transfer to ordinary prisons—sometimes after a few months—that the detainees were able to inform their families of their whereabouts.

Of the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch, 12 said that security forces tortured them, and that although some of them had formally complained about this, the authorities had not opened any investigations into their claims. According to them, the most common torture method is beating and kicking on all parts of the body, especially beating on the soles of the feet (falqa). Other forms of torture detainees described included sleep deprivation and being forced to stand for long periods. To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, the Syrian government has not conducted any investigation into these torture allegations. In addition to physical torture, 18 Kurdish activists told Human Rights Watch that security services insulted them and treated them in a degrading manner, and 14 complained about appalling detention conditions.

Most of those detained were referred to military courts for prosecution—a practice that is allowed under the Emergency Law. The judicial authorities have at their disposal a number of broadly articulated criminal provisions that allow punishment for a range of peaceful activities, including legitimate exercise of freedom of expression and association. These include (i) provisions that criminalize issuing any calls that can be characterized as “inciting sectarian, racial or religious strife” (article 307 of the Syrian penal code); (ii) provisions that criminalize “any act, speech, or writing” that can be construed as advocating “cutting off part of Syrian land to join it to another country” (article 267); and (iii) provisions that treat “any gathering of more than seven people with the aim of protesting a decision or measure taken by the public authorities” as a riot that is punishable by jail for between one and twelve months (article 336).

The Syrian authorities also have a legal trump card. Syria’s penal code criminalizes joining “without the permission of the government any political organization or social organization with an international character” (article 288 of the penal code). This includes the fact that there are no legitimate Kurdish political parties in Syria. There are nearly a thousand political prisoners including human rights activists who are subjected to arbitrary arrest, torture, inhuman and degrading treatment in prison, and unfair trials – partly because of this. They include leaders of political parties, and other men and women such as Nazlia Katchel, Tahsein Mamo who have both disappeared without trace after being detained three years ago. Some men and women have been sentenced to prison sentences of several years. The harassment of Kurdish activists continues even after their release from detention.

Since there is no political parties’ law in Syria, none of the political parties—let alone the Kurdish ones—are actually licensed. Accordingly, all members of Syria’s Kurdish parties are vulnerable to arrest and sentencing at any time. The Kurdish Left Party in Syria issued a statement commenting on this issue after the security services detained general secretary Muhammad Musa:

Everyone knows that there is no party law in Syria and in the absence of such a law, all the parties and political forces are unlicensed parties, including the Ba`ath party, which gets its legitimacy from its control of power…. This keeps a sword of Damocles over the neck of all political parties under the excuse that they belong to an unlicensed secret organization.6

The Syrian government has justified its crackdown by accusing Kurdish activists of “seeking to divide Syria.” In itself that is not enough to justify interference with freedom of association or expression, which covers peaceful campaigning for autonomy or even secession. In any event, all Kurdish political activists interviewed by Human Rights Watch have stated that their parties do not advocate for secession from Syria, but are rather seeking recognition of their status as Syria’s second ethnic group and are pushing for democratic reforms that would allow the Kurds to effectively participate in the governance of the country.

CONCLUSION

Six years after the riots of 2004, Syria should address the underlying grievances of its Kurdish population, rather than try to repress manifestations of those grievances. Democratic and human rights reforms in Syria that improve the situation for Kurds and non-Kurds alike would go a long way toward alleviating the tension between the Kurds and the Syrian state.

The Syrian authorities to cease the practice of arbitrary arrest release all those detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression and association, repeal provisions in the penal code that criminalize peaceful political expression, enact a political parties’ law, and repeal the emergency law. The Syrian government should also recognize the rights of Kurds as a minority to enjoy their own culture, use their own language, and actively participate in the public, political and cultural life of society. To those ends, the government should set up a commission tasked with addressing the grievances of the Kurdish minority in Syria, and make public its findings and recommendations.

The international community can play a constructive role in promoting the rights of Kurds in Syria. So far, Syria’s crackdown on Kurdish activists has generally gone unnoticed internationally. This lack of interest by international policymakers has many causes, including the remoteness of the areas inhabited by the Syrian Kurds, restrictions imposed by the Syrian authorities, and the international community’s focus on Syria’s role in regional politics. However, ignoring the treatment of Kurds in Syria will not make the problem go away. The international community, in particular the United States and the European Union, which are both currently engaged in substantive talks with the Syrian government, should ensure that human rights concerns, including the treatment of Kurds, are part of their discussions with Syria.

Finally, we call for action to be undertaken by the Syrian Government in order to fundamentally change the situation for its Kurdish populations for the better. One crucial step is to re-write the Syrian Constitution by acknowledging the existence of all peoples in Syria including Kurds – as the second largest nation in the country.

Other necessary steps are:

1) Reform of the system of the Syrian Arab Republic to a Democratic Republic of Syria.

2) The introduction of a new constitution, consistent with democratic norms and encompassing international human rights that recognise all peoples including Kurds and other minorities such as Assyrians and Armenians, and for the military services to confine its task to protecting public security rather than being involved in politics.

3) A new law on a democratic basis to pave the way for a multi-party political system.

4) Parliament to be representative of all peoples, ethnic minorities and religions.

5) An end to the ongoing State of Emergency that has been in effect since the Ba’ath Party coup on 8th March 1963, and the development of new laws in accordance with standards consistent with a modern Constitution.

6) To amend the media law to guarantee freedom of thought and expression and of the press.

7) To accelerate the development of laws that guarantees a true representation of women. in government and society, and changes to the personal status law so as to ensure the rights of women against discrimination and inequality.

8) To end discrimination against the children and their families who are currently stateless by granting them citizenship as a matter of urgency.

9) Abolishing of Decree 49

To conclude, it is of crucial importance that the Syrian government solves the Kurdish question by political and democratic means. That includes the recognition of the national existence of the Kurds in the Syrian constitution, and in our opinion – the right to self-determination.

In times of popular uprising in the Middle East, it is more important than ever that the Syrian Government listen to the voice of its peoples – and in particular to those who suffers the most; the Kurds.

ENDNOTES

1 For further background on the Kurds in Syria, see Kerim Yildiz, The Kurds in Syria: The Forgotten People (London and Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto, 2005); Amnesty International, Amnesty International Report: Kurds in the Syrian Arab Republic One Year after the March 2004 Events, 2005; Ismet Cheriff Vanly, “The Oppression of the Kurdish People in Syria,” in Mohammed M. A. Ahmed and Michael M. Gunter, eds., Kurdish Exodus: From Internal Displacement to Diaspora (Sharon, Mass.: Ahmed Foundation for Kurdish Studies, 2002), pp. 49-61; and Robert Lowe, “Kurdish Nationalism in Syria,” in Mohammed M. A. Ahmed and Michael Gunter, eds., Evolution of Kurdish Nationalism (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Press, 2007), pp. 287-308.

2 Some of the following information is based on Bashdar Ismaeel, “Kurdish Expectations Will Test Assad,” Daily Star (Beirut), July 11, 2005.

3 The following data on Hilal’s book were taken from Vanly, Oppression of the Kurdish People in Syria,” pp. 55-56.

4 Cited in “Politics & Policies: Pressure for Change Mounts in Syria,” United Press International, October 3, 2005.

5 The following data were taken from Human Rights Watch, Group Denial: Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2009). Also see U.S. State Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, “2009 Human Rights Report: Syria,” 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, March 11, 2010.

6 Kurdish Left Party in Syria, statement to the public, July 27, 2008, as cited in Human Rights Watch, “Group Denial: Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria,” p. 5.

©This paper is prepared for the CHACK International Conference, Stockholm 12 February 2011 by Kariane Westrheim, Chair of EUTCC, Associate Professor at the University of Bergen, Norway & Michael Gunter, Secretary General EUTCC, Professor at the Tennessee Tech University, USA